By Tom Reid, Vice President of Power Generation Services, ENTRUST Solutions Group

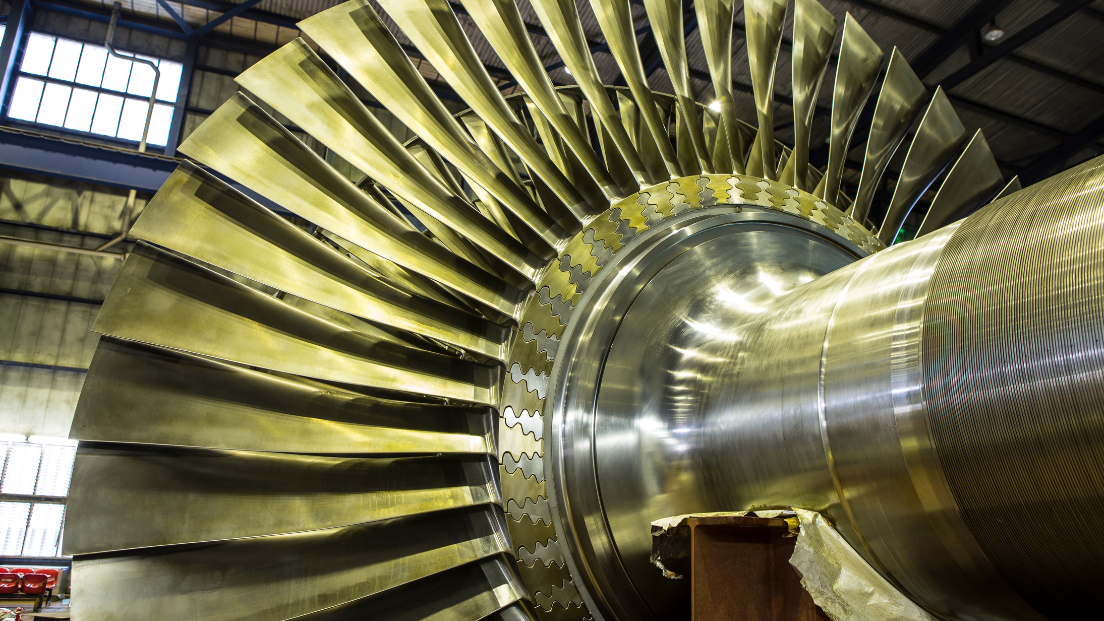

Stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in low-pressure steam turbine rotor blade attachments is a persistent issue in older fossil and nuclear units. It has often led to forced outages or extended repairs due to direct or collateral damage. Cracks initiating in rotor steeples can propagate dangerously, potentially causing blade loss and extensive damage.

Because SCC is a chronic, time-dependent failure mechanism, even older turbines that have operated without issues remain at risk. However, risks associated with SCC can be mitigated through proactive inspection programs and repair contingency planning. A thorough understanding of the causes, available inspection techniques, and repair options is critical for preventing this problem from impacting unit availability.

Certain conditions must coexist for SCC, including high tensile surface stress, material susceptibility to corrosion, a corrosive environment, and extended service time. The following key factors commonly contribute to SCC formation in low-pressure rotor blade attachments on older units:

Blade attachments are inherently high-stress areas as they transfer blade loads to the rotor. Many older designs, developed before advanced finite element analysis, were not optimized for stress concentration. This can result in very high peak surface stresses. Post-failure investigations have confirmed the critical role of stress concentrations in SCC development.

High-yield-strength materials used in early rotor designs are particularly vulnerable to SCC. Testing has revealed that crack growth rates vary significantly based on material properties and temperature, ranging from 0.005 mils/year to over 0.500 inches/year. To mitigate risks, current purchase specifications for new nuclear or fossil low-pressure turbines typically limit material upper yield strength to 120 ksi. However, many older disc construction rotors exceed this limit.

Exposure to the steam salt zone near the Wilson Line, where the transition from superheated to high-quality steam occurs, promotes SCC. This zone is near the L-2 to L-0 stages for fossil units, while nuclear units operating at lower steam conditions occur further upstream, typically in the L-6 to L-3 rows. Units with frequent condenser leaks or once-through boiler designs are especially susceptible due to poor steam chemistry control.

SCC is a time-dependent mechanism, often initiating only after decades of operation. Units with over 20 years of service life are at risk, even if no prior SCC issues have been observed. Load conditions also play a significant role. Cycling units experience accelerated crack growth, while base-loaded units exhibit slower SCC progression.

Effective inspection programs are essential for identifying and addressing SCC in rotor blade attachments. Common approaches are tailored to blade attachment designs as follows:

For these designs, visually inspect and polish critical areas, such as the hook fit or Christmas tree root, using Scotch-Brite abrasives after grit blasting. If cracks are suspected, remove a blade group and lightly polish the area to confirm the findings.

These designs are less amenable to direct inspection. Instead, employ advanced non-destructive examination (NDE) techniques like phased array ultrasonic testing. If cracking is detected, blades should be removed to confirm crack size and depth. OEMs and specialized inspection providers offer this service.

The extent of cracking dictates the required repair strategy, with the following general guidelines applied based on the depth and location of the cracks:

Light polishing can typically remove these cracks without compromising structural integrity. To minimize stress concentration factors, ensure that the grinding tool radius is equal to or greater than the original hook fit radius.

Depending on the design, cracks of this depth may be safely polished out. Care must be taken to avoid removing material from load-bearing surfaces, possibly introducing secondary issues like galling or fretting.

Weld repair is generally required. This involves removing the attachment region, performing weld buildup, or attaching a new ring to form a machined replacement. If time is limited for immediate repair, crack growth should be analyzed to determine the possibility of deferring the repair. For accurate analysis, yield strength must be verified using local hardness testing correlated to ultimate tensile strength.

ENTRUST Solutions Group assisted a client with the last-stage blade steeple SCC on a 200 MW unit that had operated for over 500,000 hours since its commissioning in 1954. The unit had experienced a mix of load cycling and stop/start operation.

During blade removal, glass bead peening facilitated magnetic particle inspection. Cracks were found in most steeples, concentrated at stress-critical locations. Crack depths varied, with most being less than 10 mils, but a few approaching 15 mils.

The repair took five days, and the unit was successfully returned to service, extending its operational life without compromising safety or reliability.

SCC in rotor blade attachments poses a significant risk to older steam turbine units. Operators can mitigate SCC-related issues by understanding the causes, adopting rigorous inspection protocols, and implementing appropriate repair strategies.

With proactive measures, and the support of ENTRUST Solutions Group industry experts, operators enable improved unit availability, reduce forced outages, and extend the operational life of legacy equipment.

Find out more by contacting us today.

***

Tom has spent the entirety of his 15-year career in the power generation industry.

In his current role as Vice President of Power Generation for ENTRUST, Tom oversees a team of approximately 100 engineers, whose expertise covers power plant equipment, modeling, and testing.

Prior to ENTRUST, Tom held turbine design and repair roles at General Electric. Tom is a graduate of GE’s Edison Engineering Development Program and holds 7 U.S. patents. He holds an BSME degree from Virginia Tech, an MSME degree from Georgia Tech, and is a registered professional engineer in the state of Delaware.