By Tom Reid, Vice President of Power Generation Services, ENTRUST Solutions Group

As environmental pressures drive the shift toward cleaner energy, many power plants are repowering with gas turbine technology and heat recovery steam generators (HRSGs) to optimize existing steam turbine generators (STGs).

At ENTRUST Solutions Group, we recognize the potential economic benefits of these projects, but also the risks involved.

A thorough mechanical and life assessment of the STG is crucial to ensuring its reliability and safety in the new duty cycle. Key factors must be considered to avoid unexpected costs and ensure a successful repowering project.

Many of the STG units that have been repowered were originally designed for baseload operation. Due to the operational flexibility integrated with gas turbine technology, many repowering projects are calling on the steam turbine generator to follow or mimic the gas turbine’s quick on/off and load changing flexibility.

The apparent heat rate from the “free steam” available from the HRSG can make the unit much more attractive in merchant plant applications. In addition, most repowering projects for environmental reasons do not have gas turbine bypass stacks, allowing them to operate in simple-cycle operation.

Therefore, the steam generated from the HRSG needs to be either bypassed to the condenser or sent to the STG for each and every gas turbine cycle. The STG must undergo a thorough mechanical condition and life assessment to determine if it is capable of operating in this manner without increasing the probability of a major catastrophic failure.

Steam turbine rotor material becomes embrittled when exposed to high steam temperatures and significant service time.

When a rotor is embrittled it becomes more susceptible to a rotor burst. In other words, the critical crack sizes required to fail a rotor become very small in an embrittled rotor – cracks might approach the size of those preexisting in the rotor. Therefore, many High and Intermediate Pressure rotors applied in repowering projects might require longer temperature soak periods to enable the rotor to regain ductility before it is ramped up to full speed, where the risks of failure greatly increase.

The need for a longer startup soak period is often overlooked in the economic evaluation of the project.

There is no rotor operating that does not have a preexisting flaw. It is a matter of how big and if the flaw is located in a high stress region of the rotor.

These flaws typically are evaluated using a fracture mechanics analysis that considers crack growth as a function of the projected duty cycle. In a repowering project that cycles, risks of bore cracking growing to a concerning size increases significantly.

Before a project is justified, you should question if boresonic inspections have been considered previously. Are there any life limiting flaws?

These concerns should be addressed prior to reuse of rotors in the train, including all turbine and generator rotors.

Larger LP blades apply very high centrifugal stresses on the blade attachment area during operation. As the unit cycles on and off, these forces produce a low cycle fatigue concern, which can greatly increase the chances of later stage LP blade cracking.

Also, on many older low-pressure rotor designs the rotor attachment areas have not been optimized with the latest finite element analysis tools since these were most likely not available when the unit was designed.

Stresses are often more concentrated than original design predictions, which increases the probability of low cycle fatigue cracking. This area must be thoroughly evaluated for remaining LCF life based on the projected duty cycle.

It should be noted that the material has memory and the damage from prior stop/starts cannot be erased. These cycles must be added to the projected cycling damage to determine remaining life.

Stress corrosion cracking concerns are focused on the stage of the turbine where the steam conditions reach the saturation dome (so called Wilson Line). This is typically in the L-2 or L-1 stages of conventional fossil-fired STGs . Stress corrosion cracking has an incubation period followed by crack initiation and then propagation.

Has the Wilson line shifted? If so, is the stage more susceptible to SCC with higher stresses or less? If the location is consistent with the prior steam cycle, what is the remaining SCC life? SCC will occur – it is just a matter of when and where. In some applications, SCC occurred as early as 100K operating hours.

Is the material used in the repowered STGs more or less susceptible to SCC? Has the project accurately identified steam chemistry monitoring requirements? Has a thorough rotor attachment inspection been made to identify preexisting flaws prior to repowering? These are some of the questions that should be asked and resolved prior to requalifying a turbine for adequate SCC life.

Almost all casing cracks (including valve bodies) are directly related to low-cycle fatigue loading experienced during on/off and load cycling. The design of casings for LCF life have only recently (last 10-15 years) been optimized with powerful 3D design tools. Therefore, almost all repowering projects that utilize existing casings will have LCF life shortfalls. It is rare for a casing with 20-40 years of service not to have some form of cracking.

As noted in Figure 1, LCF cracking occurs in locations where there are significant geometric discontinuities that cause very large stress concentrations.

Areas to evaluate are diaphragm ledges, dowel support holes and transitions from small to larger radii. Have the casings been evaluated for LCF life for the repowering project? Have major outage weld repairs been considered in the maintenance budget for the project? If the casing has been identified as a replacement item, has the new casing been optimized for the repowering project duty cycle?

Some generator rotor designs are highly susceptible to duty cycle related cracking. Specifically, the rotor tooth tops on legacy Westinghouse designs will experience LCF cracking once cycles reach a critical level.

Modifications are available to address these failure modes and must be considered in the repowering assessment phase.

Most of the time, a full rewind of the rotor will be required to accommodate the new lower stressed rotor tooth top geometry. In addition, rotor end winding blocking, pole crossovers and end winding cracking are all issues to be considered in the repowering budget.

OEMs have made some significant advancements in respect to addressing known cycling limitations.

Most of these modifications can be incorporated easily into existing generator rotor designs. In some cases, the rating of a generator may increase, requiring upgrades in insulation, winding or cooling designs.

Stator and rotor rewind life should always be considered. Rewinding, depending on duty cycle, is needed typically after 25-30 years of service. A rewind also provides an opportunity to re-rate the generator, which will always factor in as a positive in the project justification process.

Turbine blading can be the most challenging assessment for a repowering project. Inevitably, flow and steam conditions will not match the original design conditions. If the unit will be rated at a higher steam flow, the effects on blade loading and vibratory characteristics must be considered.

In many cases, some early stages in the turbine are the limiting factors from the standpoint of passing flow. If there are restrictions based on the new steam conditions, removal of these stages might be required.

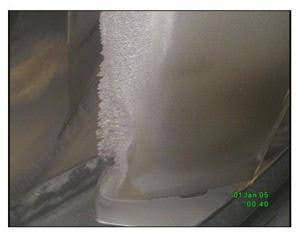

In other cases, the new cycle might have increased back-end moisture conditions. This will have a detrimental effect on the water droplet erosion characteristic of LP back-end blading (see Figure 2).

Replacement of older LP blading might be a foregone conclusion. In addition, some OEMs offer higher performance retrofit blades which will fit in the existing rotor attachment. These blades can result in a reduction of heat rate of up to and slightly more than 1 percent for the unit.

A successful repowering project depends on careful planning and a thorough assessment of the existing steam turbine generator’s ability to handle new operational demands.

Completing a realistic mechanical assessment of the proposed turbine generator is essential to ensuring safe, reliable, and realistic life projections for the new duty cycle. Without this due diligence, many repowering projects have failed to complete necessary STG upgrades, resulting in major outage costs and a scope that far exceeds budget estimates.

By addressing potential risks such as material degradation, rotor attachment issues, and stress corrosion cracking, plant owners can help ensure a smooth transition to more flexible energy production systems. Partnering with experienced professionals like ENTRUST can help identify and mitigate these risks early, keeping your project on track and within budget.

Contact us today to learn more about how we can support your repowering efforts and improve the long-term performance of your plant.

***

Tom has spent the entirety of his 15-year career in the power generation industry.

In his current role as Vice President of Power Generation for ENTRUST, Tom oversees a team of approximately 100 engineers, whose expertise covers power plant equipment, modeling, and testing.

Prior to ENTRUST, Tom held turbine design and repair roles at General Electric. Tom is a graduate of GE’s Edison Engineering Development Program and holds 7 U.S. patents. He holds an BSME degree from Virginia Tech, an MSME degree from Georgia Tech, and is a registered professional engineer in the state of Delaware.